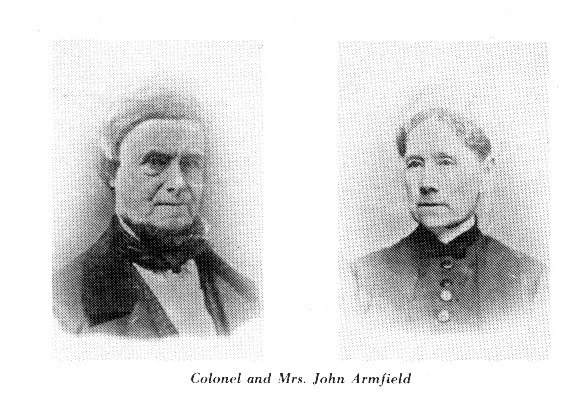

Newly Discovered Images of Notorious Slave Trader, John Armfield, and his wife, Martha Franklin Armfield.

NOTE: This is my rewritten article. The original was first published in Summer 2024 in the Sumner County Historical Society newsletter, Gallatin, Tennessee. The quality of the images in the newsletter was very poor in black and white. I rewrote the article with some additional facts and have published it here on this blog. It is important that the images be disseminated digitally in their original sepia-toned coloration for historians and other researchers. Historians and researchers are welcome to reach out to me with questions, additional images, or images of the rear of the photos. Go to the Contact Us page.—Terry Martin

———————————————-

Being a descendant of Edward Noel Franklin (1846-1909) of Gallatin, one of the Franklin nephews raised by their aunt, Martha Franklin Armfield (1815-1904) and her husband, the historically notorious slave trader, John Armfield (1797-1871), I’d been researching the family for years. I had been given many early photographs that had been in the family. My uncle has many, too, which I had borrowed and scanned.

There was one of a rather regal-looking woman, who for years I was convinced had to be one of my ancestral Hillman family relatives. On the back was handwritten, “To Nannie, Nashville, April 1878.” Nannie Hillman (1847-1923) was the daughter of Daniel Hillman (1807-1885), the wealthy iron industrialist of Tennessee and Kentucky. He had a prosperous iron store on Market Street in Nashville. Nannie married the aforementioned Edward, the Franklins being from Gallatin. Edward was also a grand-nephew of Isaac Franklin, senior partner with John Armfield of the Franklin & Armfield slave-trading firm. I had scanned the photo of the woman and stored it away digitally, labeling it, “Probably a Hillman.”

Recently, I’d become active on Find a Grave, and felt compelled to make effort to upload as many of the old photographs I and my uncle had—labeled ones or ones I could identify otherwise—onto that very useful and informative website. They included Hillmans, Goodriches, Franklins, Marables, and others, mostly families from Middle Tennessee. As I continued to have fewer labeled photos left to upload, I became increasingly curious of this unlabeled woman. What woman in my ancestry could she be, if at all, of the right age and generation of the person in the photo at the time that photo was taken in 1878? I had finally ruled, based on my research, that she was not a Hillman. “Well, if she’s not a Hillman, then maybe she is a Franklin? An aunt, perhaps?” I asked myself.

Martha Franklin Armfield. 1878, R. Poole, photographer, Nashville, Tennessee. Identified by Terry L. Martin in 2024. This is the best, clearest image of Martha known to date.

And then it hit me. “A Franklin aunt! Oh, my gosh!” On my laptop I quickly looked up the only other known close-up portrait-type image of Martha Franklin Armfield, an image that was surely reproduced from an older daguerreotype or tintype. I placed that image and my image close together on the screen. There she was: Martha Franklin Armfield.

It was obvious, but I didn’t wish to trust my own evaluation of the image. I also made a handwriting comparison from her message to Nannie on the back of the image with a letter she had written to a relative thirty years before. After thirty years, she had changed the way she made her capital “A,” but the rest of the cursive was precisely the same.

I quickly emailed the new image off to Kenneth Thomson, a local historian in Gallatin, and also to Dr. Joshua Rothman at the University of Alabama. Rothman had written the most recent scholarly work on Franklin & Armfield and the domestic slave trade, entitled, The Ledger and the Chain: How Domestic Slave Traders Shaped America, published in 2021. I had been in communication with Dr. Rothman for several years, and he had cited a couple times in his book from my own work, Love’s Young Dream: The Letters of Dr. Edward Noel Franklin to Miss Nannie Hillman, 1871, published in 2018, in particular a letter Edward wrote to Nannie, having been present the night that his uncle John Armfield died at Beersheba Springs, Tennessee in the fall of 1871. Thirdly, I sent the image to a Franklin cousin in Nashville who has been involved with me in some family dialogue with our other interested cousins in the Northeast on our ancestors’ infamous and unhappy involvement in the slave trade.

All agreed. In fact, they all knew it to be a dead ringer. I sent it to some with whom I was in touch at the historical society over at Beersheba Springs, Tennessee. Armfield had used his money from the slave trade to revamp that resort in the late 1850s for entertaining the white elite of the South a few years before the Civil War. The Armfields lived there during those years. They, too, were excited to see this new image of Martha.

So, it occurred to me, “If I have one of Martha, then really about the only people who would logically have an unknown image of John Armfield himself, would be me or my uncle.” Aside from those Northeastern cousins I mentioned, we are perhaps the ones most closely related and who have kept family memorabilia. John and Martha had no children together. In any event, I began perusing the unlabeled images we have. There was definitely one which seemed possible, but when I emailed it to the others, they all disagreed. It wasn’t a close enough likeness to the only other known photo of John, often printed side-by-side with the old image of Martha in publications, and like hers, a reproduction from an earlier image.

I knew they were right, but I kept searching. Then I started studying the face of yet another one of the unlabeled images. This one was intriguing. “Well, you know? I bet you anything…” It was placed in a photo album in the late 1800s by my aforementioned ancestors, Nannie and Edward Franklin, next to an image of Dr. John Washington Franklin (1819-1905) of Gallatin. Dr. Franklin was Edward’s father, but long before, when Edward was a child, his mother passed away, and Dr. Franklin turned Edward and his two siblings over to his sister, Martha Armfield, to raise. If this other photograph next to Dr. Franklin in the album was John Armfield, it made perfect sense. Here were essentially Edward’s two fathers: his real father and the father-figure uncle with whom he lived from childhood to adulthood, John Armfield. In addition, I knew that Dr. Franklin and John Armfield were not only brothers-in-law, but also good friends and that Dr. Franklin was the executor of Armfield’s estate.

John Armfield. About 1867, T. F. Saltsman, photographer, Nashville, Tennessee. Identified by Terry L. Martin in 2024. This is the best, clearest photographic image of John Armfield currently known.

As I did with the Martha images, I did with these other two. I placed them very closely side by side on my laptop screen. Same hair, same hairline, same Quaker type beard, though grown up to his ears in the newer image. Same smile, same eyebrows, same line between lower lip and chin, it all lined up. I felt confident.

Dr. Rothman at Alabama was convinced in an almost immediate email reply with a big, “Wow!” My Nashville Franklin cousin: “I’m convinced.” Kenneth Thomson: “No doubt,” but he also checked with a friend of his with whom he often consults on identification, himself a collector of antique images, who agreed: “No reason at all for that not to be John Armfield,” he said. The Beersheba Springs folks, too, responded positively.

As shown on the rear, it was taken by Saltsman in Nashville, Kenneth says probably between 1866 and 1868, maybe 17 or 18 years after the older daguerreotype image he thinks was from the late 1840s.

These are the best, clearest, photographic images currently known of the notorious slave trader John Armfield, and his wife, Martha Franklin Armfield.

And I’d been sitting on them for years.

For the purpose of putting faces with the names, the images are important for writers and historians in telling the story of the brutality of the antebellum domestic slave trade. The notorious Alexandria, Virginia firm, Franklin & Armfield, is considered the largest, most successful and efficient domestic slave-trading empire in American history. Operating largely in the 1830s, it was responsible for purchasing thousands of enslaved humans from Virginia and Maryland, and shipping or marching them in coffles, to the Deep South slave markets in New Orleans and Natchez to work on the cotton and sugar plantations. It was an exciting discovery on my part to uncover these two historically important photographs. But the legacy of John Armfield, raw and unglorified, is one of tragedy and the suffering of thousands.

These are the earlier images of John Armfield and wife Martha Franklin Armfield by which the comparisons were made with the new images. These images have appeared in other publications in the past. They were originally daguerreotypes or tintypes. The whereabouts of the originals are unknown. Sumner County Historian, Kenneth Thomson, believes the originals to be from the late 1840s.